Climbing Beyond Fear: Marguerite Holloway’s Journey through trees & transformation

Join us on a captivating journey into the world of trees and the profound connection we share with them, as we welcome Marguerite Holloway, author of "Take to the Trees," to our podcast. Marguerite's journey from a tree-climbing novice to a passionate canopy explorer is an inspiring tale of adventure, resilience, and personal transformation. Listen in as we explore her motivations behind writing a book that blends science, memoir, and adventure, offering a vivid portrayal of the beauty and challenges faced by our forests. Her insights, enriched by personal reflections on loss and resilience, provide a compelling narrative on the intricate bond between humans and nature.

In this episode, we reflect on the metaphorical and literal strength discovered through tree climbing. Marguerite shares how confronting her fear of heights led to a transformative experience that intertwined physical challenge with emotional healing. This journey helped her process personal grief and reframe her climate anxiety, highlighting the power of community and collective action. Discover how women in the traditionally male-dominated field of tree climbing are tackling environmental issues with agency and care, emphasizing the importance of facing daunting challenges head-on.

Marguerite's journey is a testament to the power of storytelling in advocating for nature. We discuss the interconnectedness of people working towards environmental and social change, drawing parallels between mycelial networks and the human efforts to nurture our planet. Explore how creating art and stories can raise awareness and drive engagement with pressing environmental issues. We also touch on accessible ways to foster a deeper relationship with trees, even in urban settings, and the importance of creating legacies of care for future generations. Join us as we celebrate the enduring connection between people and nature, and be inspired by the euphoria of creating something meaningful.

This week’s episode was written and recorded in New York City on the native lands of the Lenapee tribes.

This episode was produced, written and edited by Jonathan Zautner.

To learn more about our podcast and episodes, please visit treespeechpodcast.com and consider supporting us through our Patreon — every contribution supports our production, and we offer gifts of gratitude to patrons at every level. If you liked this episode, please rate and review us on Apple Podcasts or share it with a friend. Every kind word helps this forest grow.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

00:08 - Jonathan (Host)

Reaching for one branch at a time, pulling myself higher and higher, one step then another, as the ground drifts away beneath my feet. Above sunlight sifts through a lattice of green and every leaf seems to whisper its own small story. When I was much younger, I found such comfort and accomplishment in the canopies of trees an accomplishment in the canopies of trees, climbing felt adventurous and daring, athletic, artistic and brave. I'm Jonathan Zautner, and this is Tree Speech. It's been a long time since I've felt the exhilaration of climbing a tree, but in today's episode we listen for what the treetops can still teach us about beauty, urgency and care, with someone who began climbing trees as an adult and whose life reminds us of the fearlessness we all need to grow.

01:18

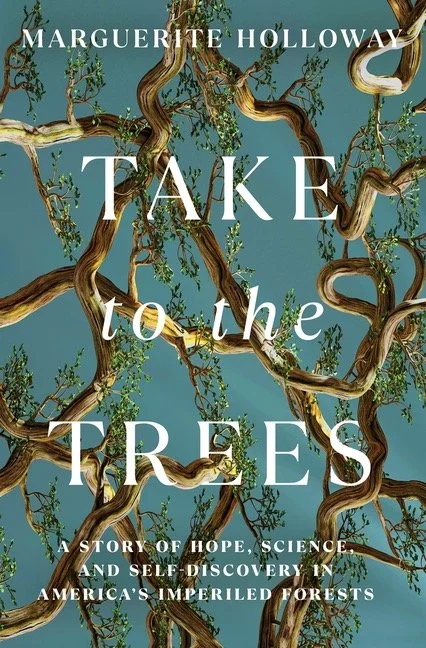

Our guest, Marguerite Holloway, is an author, journalist and professor whose latest book Take to the Trees: A Story of Hope, Science and Self-discovery in America's Imperiled Forests, is a vivid blend of science, memoir and adventure. She chronicles her transformation from tree-climbing novice to passionate canopy explorer, guided by twin arborists, Bear and Melissa Levangie. Along the way she learns not only the skills and science of climbing but also urgent truths about the challenges our forests face and the quiet understanding that trees, like people, hold histories, grief and resilience in their rings.

Marguerite weaves powerful personal reflections on loss, resilience and the enduring bond between people and trees, with lyrical reportage that balances alarm with hope. She has written for the New York Times, the New Yorker, Audubon, wired and Scientific American. Today she serves as professor and director of science and environmental journalism at Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism and is also the author of the Measure of Manhattan, the story of John Randall Jr, the surveyor who laid out New York City's 1811 grid plan, and of the researchers who use his data today. Now she brings that same depth and wonder into the branches of our forests and our lives.

02:58

In our conversation, we'll explore the research and writing of Take to the Trees, the unexpected lessons of climbing high into the canopy and what her journey taught her about the resilience of forests and of herself. So lace up your boots, look up toward the branches and join us as we take to the trees with Marguerite Holloway. Let's listen.

Well, hello, Marguerite. It is so wonderful to have you on the podcast today, on this hot July day, but I'm excited to discuss your book. So thank you for joining us.

03:40 - Marguerite (Guest)

Thank you so much for inviting me. I'm really looking forward to this conversation.

03:45 - Jonathan (Host)

Me too. So I'm going to start with where I was introduced to you and to your book Take to the Trees, and that was at the book launch which happened on the Upper West Side at Book Culture. And I was intrigued by the book and by you and so I went there to hear you read from the book and to learn more about it. And I've been thinking a lot about tenderness lately and sort of this need for more tenderness in our world and for each other and patience, and I was really struck by the amount of tenderness in that room from you and for the content and for the passion that you have for this book that was being launched into the world, but also from the people that were there. I gathered from all walks of your life students, colleagues, family, tree scientists, other climbers, tree people and I just wanted to hear from you what that felt like to have all of those people in one place in the room, celebrating you and your work and trees in this way.

04:56 - Marguerite (Guest)

It was incredibly moving and I think it might choke me up a little bit.

05:01

But I was so nervous about the reading and also in some ways about the book, because for me it is such a departure in terms of the way I've written in the last couple of decades and just every second another person came in. I just was like, oh my God, you, oh you. You like just this incredible joy about people who had made the effort to be there and this incredible sense of what I think connects to tenderness, but a sense of safety and a sense of connection and kindness, and I just felt that from everybody in the room and it transformed my nervousness into this kind of euphoric energy that was really wonderful by the questions, some of them from people who had been with me through this whole process and knew some of the very particular details and things that I had been thinking about, and then others that were broader but just so creative and engaging and made me also realize that the book which I know abstractly, but then any piece of writing, different people find different things in it, and that that is very moving.

06:32 - Jonathan (Host)

Yes, yes, and sitting there was a moving experience in itself. So let's talk about the book and about your sort of entry point into it. You've described attending the Women's Tree Climbing Workshop as a turning point where fear of heights, grief and a career crossroads all converged for you, what made you say yes to the climb? And once you were up in the canopy, what shifted for you internally?

07:03 - Marguerite (Guest)

I think I may have mentioned this before, but I had been writing about climate change and I was working on a story for the New York Times about climate change in New England forests and as part of that I heard about Bear and Melissa, actually from someone who works for the International Society of Arboriculture in New England.

07:27

And then I met them and I can't imagine saying no to anything that they would propose.

07:34

They are just so present, so kind, so aware of the world and of people and of the natural world, the non-human natural world, that when they told me about the workshop and then they found a space for me, someone had, I think there's often a very long wait list and the one I had wanted to take was filled up, and then there was a cancellation and they let me know and I think it took me maybe, you know, three or four minutes to decide yes. And so I knew that it was going to be very challenging because of, as you mentioned, I had this incredible fear of heights and I'm on the older side not, I think, I'm relatively physically fit, but taking on something that I knew was going to be very physically challenging and that was going to really push me, you know, was daunting up in the canopy. As you say. All sorts of things happened to me. They didn't happen immediately, they happened over time, over going back to these same trees and to this same place several times. The transformation for me was slow, but it did happen, yes.

08:59 - Jonathan (Host)

Well, and the book is about that self-discovery, but it also pertains to your relationship with your late mother and brother. Through the lens of your time with trees, could you tell us a little bit about how the act of climbing, physically ascending into this canopy, how did that shape your experience of grief and healing?

09:24 - Marguerite (Guest)

I think there's something about feeling that you can't do something, that you just it is not possible for you to do something and then, within a few seconds or a minute or however long it takes, you do that thing, you do that thing.

09:56

And it made me feel this incredible sense of strength and centeredness and a sense that, yes, I could deal with things.

09:59

I could face things, not just physical things and challenges, but also emotional and psychological challenges, and they were all bound together and I think we are all bound together in this way. The physical expression of things is so connected to the way we think and the way we feel, and I think many of us feel most alive when there is some kind of fusion, when those realms are all sort of operating together, even if we don't always recognize that they're operating together in that moment. And overcoming the physical challenges led me to overcome these blocks, I think, in emotion and being able to face a lot of the loss and grief. And I had this experience and I write about it in the book but being in the canopy, feeling this incredible joy and then suddenly feeling these waves of grief and sadness, and it was all connected. But I feel as though if I hadn't pushed myself and realized these strengths in myself, I wouldn't have gotten there in the same way.

11:15 - Jonathan (Host)

Right, and reading about that process is quite inspiring, and the way that you detail it really takes us through, piece by piece, the amount of time, the amount of patience and the process that healing undergoes. A third aspect of the book with this personal journey is climate change, and you've written that climate change feels like a trauma that keeps gathering power because we won't look directly at it. How did climbing trees help you reframe or manage climate anxiety in real time?

11:56 - Marguerite (Guest)

Well, I think that, in the same way that I couldn't maybe look so directly at the grief around the loss of my mother and my brother, I feel it is very similar and I feel as though we as a society do not want to. Well, that's not true. That's an overgeneralization. There are many people In fact I think most people are looking as directly as they can at this huge issue, but I think that's very different than engaging with it in a very active everyday way, and the longer we put off looking at it directly and acting as if it is perhaps the most important thing, the longer it just snowballs and gathers force.

12:51

And I do feel that there is a lot of connection between facing things as an individual and facing things as a society, and I think climate change very much resides in that realm. Yeah, and I have to say also, it was overwhelming doing all this research on what climate change is doing to trees and then what pests and diseases are doing, and at times it was really very consistently dark and difficult. And it was in meeting people who are trying so hard at all these different levels at the level of themselves, their family, their community, their forest, their profession, their research, their policy efforts, me feel in a much broader community of people who are looking very directly at it and who are feeling grief but who are also feeling agency, and that is what the book and climbing did for me.

14:06 - Jonathan (Host)

I understand, and the importance of community and collective care is apparent throughout every page of the book. Let's stay there for a moment. The book highlights the work of women in what's long been a male-dominated field. What lessons, would you say, emerged from your time at Camp High Rock and throughout the book, and how did those women influence your view of the broader climate movement?

14:37 - Marguerite (Guest)

Again, I think it really has to do with people understanding their own power and learning that power and recognizing it in a setting in which they feel safe and cared for, because I think in those settings we really do our best.

14:58

We face things, we are more open to things, we are less defensive.

15:05

And the process of being in the workshop and observing so many other workshops that I wasn't an active participant in but was sort of more reporting on and talking to the women and made me just see and many good teachers know this like if you create a space in which people feel safe, they're willing to take all sorts of risks intellectually and physically that help them grow, and that's one of the big things that I took from the workshop.

15:40

I also took this amazing sense of it doesn't matter where in the country you are. You are, if you've gone through that workshop, part of this like huge network of people who are all doing really important things, whether it is trying to explain to homeowners the importance of the trees and how they can make better choices in terms of what they want to take down or what they want to plant, or, you know, somebody just supporting someone who's had a really crappy day on a crew that doesn't appreciate them, or connecting researchers who are coming at the same problem in very different ways, and that network I think we tend to forget, because there is so much fragmentation in our society that we read about constantly that there's actually also a lot of cohesion in our society and a lot of people who are very connected around the same issues and do express a lot of care, and I think it's just really really important to remember that.

16:48 - Jonathan (Host)

Yes, it's powerful. I've heard it's referred to as sort of a mycelial network of climbers, because they're all interconnected and feeding one another and nourishing each other and the Earth. And it's honestly, I believe, through that power that real change will happen, the change that is needed for humanity.

17:10 - Marguerite (Guest)

I agree, and Bear and Melissa explicitly referred to it as the mycelial network of the Women's Tree Climbing Workshop.

17:18 - Jonathan (Host)

I love that imagery you feel like you're part of something, as I said, powerful but creating real change. As a Columbia journalism professor and longtime reporter, how did blending memoir, science and immersive adventure shift your writing process? Did it uncover insights you wouldn't have found through traditional reporting, and how was that process to write in a different way than you had previously done?

17:49 - Marguerite (Guest)

It was very, very difficult for me and I have thought about it a lot, because I was a comparative literature major and I did a lot of fiction writing when I was at university and I really for a long time thought that that was the way that I would go. And I ended up focusing on science and public health, in large part, I think, because it needs a lot of translation those realms, because people are intimidated by science although none of us should be, and there's a lot of opportunity for using description and imagery and narrative to make those worlds feel, those realms feel much more accessible. That said, I turned away from fiction writing and, although I was incorporating those components of writing that I really love in terms of imagery and translation and description, I was doing journalism in a very traditional and very sort of classical science journalist way and I have always discouraged my students from using I. There has to be a very, very good reason for it. You really need like and braiding it with science journalism.

19:13

And it was a very, very difficult process and it took a lot of encouragement on the part of my editors, in my family and at Norton my amazing editor at Norton, Tom Mayer, and my husband Tom and my kids, Auden and Julian. It was almost like a musical process where something had gone on too long maybe a scientific description and felt as though the braiding with the personal or with the memoir wasn't happening at the right rhythm, at the right pacing. So I would have to go back and all sorts of associations happened in that going back. That, I think, would have never happened if I was writing in the way that I have for the last several decades. Associations would just come almost in this. It was kind of wild when it happened and I can't really explain it, but there were connections that I was much more open to because I was writing about these memories and my family and my own experience that I just don't think I would have made otherwise.

20:51

I don't know quite how to explain that. I was talking with my editor about it at one point and I mentioned this artist that my husband and I love. Her name is Isabella Ortiz and she describes and I think many painters do this of sort of she approaches her canvas or her paper from one side, then she turns it and she comes in another side and she turns it and she comes in another side and she turns it, she comes in another side and it's very nonlinear. And that's exactly what my process was like. Usually it's very linear and it was not at all this time. I was coming in here, coming in there, turning it, leaving it, and that all made for something quite different that I'm very happy with.

21:34 - Jonathan (Host)

Yes, that's fascinating. We talked about the book launch. Did it feel different putting this into the world as well, because it contained more personal information and parts of you that you were now sharing with the whole world.

21:51 - Marguerite (Guest)

It did feel different, but on the other, it felt very scary, and I think that's part of why I was so nervous. I mean, part of it is just being in front of a group, a crowd that always can make one nervous, or make me nervous, but at the same time it is the most me thing I've ever written, and I feel so grateful to have been able to have the freedom to approach this book in this way. And so, yes, it did. It scared me a little bit, but I also just feel this enormous sense of gratitude and joy about having written something that really feels, for the first time, fully in my voice, fully me.

22:41 - Jonathan (Host)

All of the elements of your world sort of came together to produce this beautiful work. As you were writing then. Drawing from all of these different components, how did you balance urgency with wonder in your writing, especially when facing what feels like irreversible ecological change? And we've heard a lot about how we present or how climate change is presented, and the importance of story within that, how people learn about climate change and what needs to happen. So I wonder your thoughts on what responsibility storytellers may carry in this moment as we're looking at the work that needs to be done.

23:27 - Marguerite (Guest)

I think storytellers have an incredibly important role to play and not necessarily on the tracks that we usually is happening, I think is extremely valuable and I think sometimes these very landscape or bird's eye scale understandings, they're critically important.

24:05

But it's also the understanding of what is right next to you and right around you and there are people who observe closely pretty much I think everyone observes closely given the opportunity and that that be celebrated and that that be presented in a way that feels accessible and allows people in, I think is just absolutely essential. And what you said about urgency and wonder, I think is really fascinating because again and again, scientists and one of the researchers in the book says this, but it's horrifying what he's seeing happen to, for example, the beech trees. The forests are looking completely denuded and this incredible food source is disappearing. And yet he is so driven to understand why this is happening, how this is happening, the intricate, granular details of these nematodes, and he has this incredible curiosity and wonder about understanding these processes, at the same time that he has this incredible sense of urgency and incredible clarity and grief about what is happening to the forest. I think that fusion makes a lot of sense, that you can have all those things and in fact it's very motivating to have all those things.

25:43 - Jonathan (Host)

Yes, I believe that too. Sort of everything can happen all at the same time. All of these contrasts can be true. Throughout the book there's a narrative thread that involves you uncovering trees that you learned were important to your mother, but only had found that they were important to her after she had died. Could you talk a little bit about that after she had?

26:12 - Marguerite (Guest)

Yes, so the germ, or the seed of the book, really began right after my mother died and I was cleaning out her apartment and I thought I had seen everything that there was, because I had moved her from one apartment to another, I'd redone her apartment, I'd taken care of her. And this tree journal I had not seen and it just blows my mind that I hadn't found that before. But in the tree journal for about 11 years she chronicles all these trees that she meets and writes about their natural history and sometimes she draws them.

26:49

And I knew that she loved trees because she had had my brother and I spend a lot of time out of doors and try to learn, had us learn the names, tried to teach us the names of all the trees. So I knew she had a lot of deep knowledge but I hadn't known that it was, that she had sort of brought her artistic and naturalist sensibility to chronicling that in any way. So it made me feel hugely connected to her to start to see, to observe as closely as she did some of the trees that I was getting to know. It made me feel like I understood her even though I've always known she was a naturalist and made me understand her more deeply, and I'm just incredibly happy about that and feel very lucky to have discovered that journal when I did actually, you know, because she had dementia, and if I had discovered it in the thralls of her dementia, I don't know if we would have been able to communicate it about it in some way.

28:00 - Jonathan (Host)

Yeah, where is the journal now? Do you have it in your possession or where?

28:05 - Marguerite (Guest)

I do. I think it is right here. Yes, it is right here. I keep it right near me and I look at it occasionally, and it is right here. Yes, it is right here. I keep it right near me and I look at it occasionally, and it's right here. I think I might still do something with it, because there were many trees that she wrote about that I didn't write about in the book and I didn't share any of her illustrations or any of these images of the leaves that she taped in, and I am really curious about the natural history description she got. I found one reference to a library at the University of Berkeley, california, berkeley, and I'm really curious what texts she was in reading. So that is something I might look into going forward, because they're not the standard texts, the field books and field guides that I've looked at.

29:01

There's a very different language.

29:03 - Jonathan (Host)

It's amazing.

29:04 - Marguerite (Guest)

There might be more to do, and it feels sort of like she guided this process.

29:08 - Jonathan (Host)

It's really beautiful. Her story and the story of the journal is interwoven with, as we talked about, urgency and wonder. It really creates those moments to breathe, to gain perspective and to feel energized to do the work that needs to happen to make this world a better place. You talked about your mother's illustrations, which I would love to see, so I hope that you do something with that journal one day when the timing is right, but I must also mention the gorgeous and inspiring illustrations that appear throughout this book.

29:47

They are magical, and I wonder if you could tell us how you hope the illustrations relate to your writing and maybe what that relationship or dialogue is.

29:58 - Marguerite (Guest)

Oh, that I mean Ellen Wiener is just so brilliant and I wanted illustrations that had a lot of emotion to them and a lot of movement and power to them, because this book is about so many things, but the trees as characters who are sort of trying to tell a different story or different facet of climate change, they come forward and take the stage and I wanted the the illustrations to have as much like, to have as much presence as possible.

30:37

And Ellen kept saying that she was not a traditional botanical illustrator and that I didn't really know what I was doing. And I kept saying I do know exactly what I'm doing, like you just see them and they move and they're evocative, they're like poems and she has a very, very strong connection to poetry and to literature and I'm so thrilled. They work with the text but they're also their own story and we very much worked with a designer to have them coming in and the text go around them in places where that felt right. But I feel like you could get a sense of light and dark and power and hope and despair by looking at the illustrations just by themselves.

31:38 - Jonathan (Host)

Yes, yeah, you definitely do. It is Now that you say that it is visual poetry and I'm glad you convinced her to be a part it really completes.

31:42 - Marguerite (Guest)

Oh, me too, I am so lucky.

31:44 - Jonathan (Host)

That's gorgeous. We touched on this a little bit, but how has your perspective on nature, storytelling and humanities plays? This is a big question in the world evolved since finishing the book, and what are your next questions for yourself, for science or for the forests?

32:03 - Marguerite (Guest)

I feel as though the book helped me of align the personal and the societal.

32:13

It made me feel like it's okay to be explicit about all these realms being connected.

32:20

At least for me, that felt very right. My next steps, I don't know. I'm really curious to go back to a bunch of the incredible researchers who I spoke with during the course of the book and sort of find out how they're doing right now, because the Forest Service has been so hard hit, the Park Service has been so hard hit, science research generally has been so hard hit. The EPA, like everything that supports an understanding of climate, yes, noah and the research that really can help us find our way in the future is really under threat. But I don't know the specifics and that is something I'm hoping to return to and to write about, maybe more as articles or as essays for the next step, and I also really want to keep working with people like Ellen, anybody who wants to, with colleagues at Columbia, like at other universities, other artists, to find ways to tell the stories, as you were talking about earlier, that connect people to the changes that are happening and make it really clear how dire they are, but how much action and engagement can make a difference.

33:48 - Jonathan (Host)

Right, it's the most important at this point, which leads me to ask you what advice do you have for listeners who want to cultivate a deeper relationship with trees, especially those who don't live near big forests or aren't ready to do a tree climbing workshop? Are there accessible ways to take to the trees wherever a person may be?

34:14 - Marguerite (Guest)

I think there are, and I think also the Women's Tree Climbing Workshop is very aware that some people don't need a whole weekend to do this training. They might want to just spend a day in the canopy and sort of not have to learn all the knots and the equipment, but just get up there and to be there. So I think that there are going to be opportunities to do that through them as well, and so those might be an easier on-ramp than committing to, you know, learning how to climb, although I would, you know, strongly encourage that too. I live in New York City. I don't live in a forest.

34:53

I spend as much time in forests as I can, but you can start just closely observing a tree outside your house or your apartment building or on the street or in a park. You can engage with community groups who are really working on greening suburban and urban spaces. So I don't think you have to be in the forest to take to the trees. You just need to slow down a little bit and look carefully and observe what's happening and think about maybe who is the caretaker for that tree. Could you become the caretaker for that tree? Can you engage other people on your block to be caretakers for the trees. I've mentioned this in some of the interviews I've done, but I attended a course called Citizen Pruners that is run by Trees New York, and I took that class, which was amazing, and I have still yet to take my exam to become actually a citizen pruner, even though I talk about this group all the time and what I learned in it.

36:00 - Jonathan (Host)

You've been busy.

36:01 - Marguerite (Guest)

I hope I actually do this soon, but that's one example. That's a New York City group that has thousands of members and people who are looking at the trees, who have learned how to prune them in a safe way, who can look at the soil, who can look at the tree pits and who can really start to think about caretaking. And I think that you can do it anywhere. It doesn't have to be in a forest or at the scale of a whole woodland.

36:32 - Jonathan (Host)

Right, it's starting wherever you are with whatever you have. So of course, we suggest that everyone go out and purchase your book at their nearest bookstore or get it at the library. But if people want to know more, where can they find you, especially to know about your upcoming tour for the next few months?

36:55 - Marguerite (Guest)

I have a new website that one of my friends, former student, designed, janelle Redka. It's absolutely beautiful and it's margueritehollowaycom and I'm putting all of the book tours on there. I also put it on LinkedIn yesterday the whole list of them, but the links to the actual bookstores are up and I will keep updating that and adding podcasts and interviews and things when they appear. I also just really like talking to people, so I'm very open to people reaching out. I had the most beautiful letter from a gentleman, I think in Fairbanks, who works with wood. He told me the stories of all of the trees around his house and then in his home and all the things that he had built with these different trees and sent me pictures. It was one of the most beautiful, beautiful notes. Anyway, I love hearing from people, so they can do that through the website or through my Columbia. I have a Columbia faculty website too.

38:04 - Jonathan (Host)

Wonderful, and I'm not surprised that you have received mail like that, because your work, including this book, take to the Trees is very inspiring, as is this conversation, so thank you so much for being with us today. Marguerite, I know you talk about sort of the care and safety that people need to feel in order to go out and make a difference and, honestly, your work really lends itself to feeling held, to feeling safe and to feeling empowered to go out and make a difference. So thank you for your words and your inspiration. We'll be looking out for your book and for your tour and for all of the work to come. Thank you again.

38:47 - Marguerite (Guest)

Thank you so much. This was a really really lovely and wonderful conversation and I really appreciate it, Thank you. It was all our pleasure and I really appreciate it, Thank you.

38:55 - Jonathan (Host)

It was all our pleasure.

Marguerite's journey leaves us with a quiet truth when we feel safe, truly safe, we can open, we can stretch higher, root deeper and see the world more clearly. Tenderness is not only an emotion. It's a space we create for one another, a shelter where growth becomes possible. Here, on the ground, the trees still stand tall above us, their branches reaching out, their roots holding steady, reminding us that safety and care for ourselves, for each other, for the wild places we love, are not just the soil beneath our feet, but the very roots that lift us toward the sky. Marguerite carries with her a powerful reminder from her mother, a tree journal, a legacy of care and witness that lives on through her. In the same way, the care we offer now through our stories, our actions and our love for the natural world, becomes the legacy we leave behind, a gift for generations yet to come. And it is through story, the stories we tell and the relationships we nurture with trees and the earth that we find the spark to act, to protect, to restore and to build a healthier climate and ecosystem for all who share the earth. Because to take to the trees is to step forward with courage, to become part of a legacy that nurtures life and lifts us all towards something better.

Thank you to Marguerite for showing us one way to make this possible, for reminding us of what we once knew when we could so easily climb a tree without a care, and of the great responsibility we now carry for them. Until next time, be gentle with yourself and keep listening, for in the rustle of leaves and the stretch of branches, the trees are still speaking, and if we're quiet enough, we might just hear the future calling.

41:22

This week's episode was written and recorded in New York City on the native lands of the Lenape tribes. This episode was produced, written and edited by Jonathan Zautner with Dori Robinson. To learn more about our podcast and episodes, please visit treespeechpodcastcom and consider supporting us through our Patreon. Every contribution supports our production and we offer gifts of gratitude to patrons at every level. If you liked this episode, please rate and review us on Apple Podcasts or share it with a friend. Every kind word helps this forest grow, and thank you for listening to Tree Speech today.