Embracing Tree Time: STillness, Transformation, and the nature of becoming with Sumana Roy

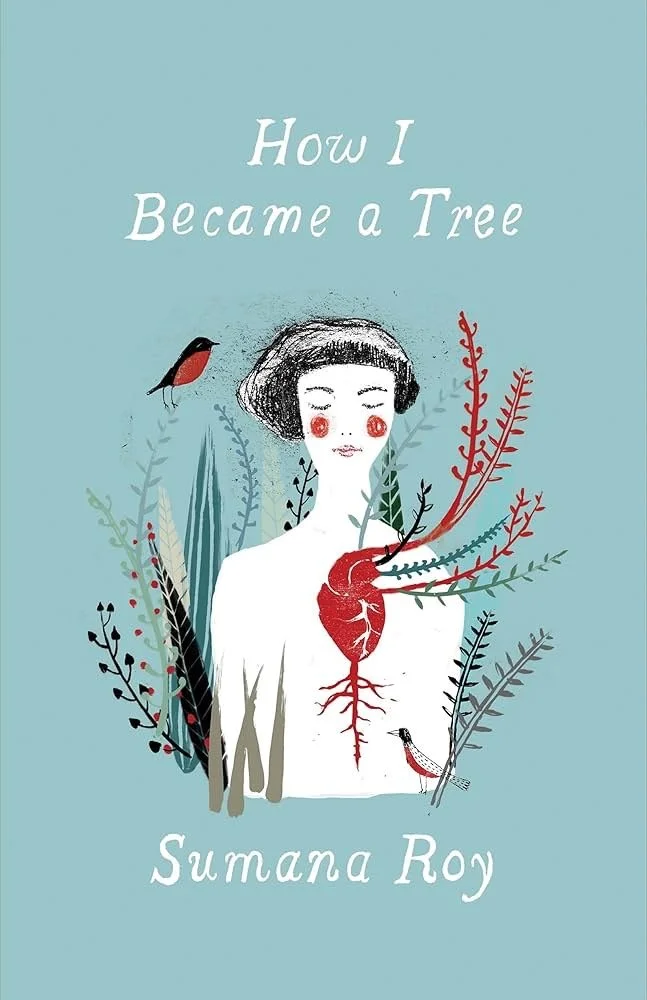

What if transforming into a tree was not a punishment but a conscious, enriching choice? Join us as we explore this intriguing concept with our guest, Sumana Roy, author of "How I Became a Tree." Sumana shares her personal journey towards identifying with trees, driven by a longing to escape the emotional turbulence of human existence. Through our conversation, we uncover the profound philosophical and emotional connections humans can form with the natural world and challenge the notion of transformation by finding peace and meaning in adopting a tree-like existence.

As we contemplate the notion of "tree time," a fascinating paradigm shift emerges—one that offers a conscious escape from the frantic pace of modern life. Through personal stories and reflections, we examine how embracing slowness and stillness can foster creativity and a heightened sense of awareness. This episode invites listeners to rethink their perception of time and attention, urging us to overcome "plant blindness" and appreciate the often-overlooked wonders of the natural environment that surrounds us. Join us in this captivating episode to discover how these themes resonate with our everyday lives and our roles as caretakers of the earth.

This week’s episode was written and recorded in New York City on the native lands of the Lenape tribes.

This episode was produced, written and edited by Jonathan Zautner.

To learn more about our podcast and episodes, please visit treespeechpodcast.com and consider supporting us through our Patreon — every contribution supports our production, and we offer gifts of gratitude to patrons at every level. If you liked this episode, please rate and review us on Apple Podcasts or share it with a friend. Every kind word helps this forest grow.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

00:06 - Jonathan (Host)

Across cultures and centuries, myths of humans transforming into trees appear again and again. When I first encountered these stories in Greek mythology, they unsettled me. Daphne becomes a laurel to escape Apollo's relentless pursuit. Myrrah, burdened with sorrow and shame, transforms into a weeping myrrh. Andriopy, once a princess, now a mother, plucks flowers from a lotus tree, unaware it was once the nymph Lotus. The tree bleeds and at once her own body begins to change Before her husband and sister's eyes. Her face disappears beneath bark, her arms stretch into branches. With her last words, dryope begs them to raise her son with reverence for trees, for any tree, she warns, may be the dwelling place of a goddess. As a young person, I read these tales as punishments, fates worse than death, to be rooted, silenced, turned to wood. But my long-held perspective recently shifted after reading how I Became a Tree by Sumana Roy. A luminous blend of memoir philosophy and literary history, roy invites us to imagine tree time a slower, more patient rhythm of being that stands in contrast to the speed and violence of human life. Her book reminds us that trees have always been more than background they are teachers, companions and models of endurance and stillness.

01:58

In today's episode, I speak with Sumana Roy about what it might truly mean to become a tree. I'm Jonathan Zautner and this is Tree Speech, and here is a bit of background about our guest. Sumana Roy is a writer, poet and professor of creative writing at Ashoka University in India, where she also works with the Indian Plant Humanities Project. Her essays, poems and stories have appeared in journals such as the Paris Review and Guernica, and she is the author of several books, including the acclaimed how I Became a Tree, which we discussed today, as well as the novel Missing, the poetry collection Out of Syllabus and my Mother's Lover and Other Stories.

02:49

This summer, Sumana joined me from the Himalayan foothills while I spoke from New York City. You may hear a bit of background sound from both our worlds, which I hope will add to the richness of this conversation. Let's listen. Welcome, Sumana. I am so honored to speak with you today about your life and your books, including how I became a tree and here on Tree Speech. We have explored speaking for and with trees, communing with trees, listening to trees and honoring, studying and including trees in many facets of our lives, but we have never explored becoming a tree across two instances in literature, where people either became or were turned into trees, and both were violent and upsetting to me and so I sort of stayed away from the subject matter. But reading your book and now speaking with you, I think, will definitely rewrite my fears of becoming a tree. So I would like to start with the question of what drew you to the idea of becoming a tree not just writing about trees, but actually identifying with them.

04:10 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

I wish I knew Jonathan. Perhaps it's a good thing I don't actually so I really don't know how my analogical imagination and behavior came to be, came to exist. I have no memory of writing about plants with any degree of conscious focus or attention, but let me try and tell you how I began writing it. I cannot specify what it was, you know, that had made me feel injured by human life, by the social, by things around me, human life by the social, by things around me, and I wanted to abandon the social. Could I live like, I'd asked myself, a ceiling fan, a cell phone? No, I didn't want to be a machine. No, I wanted to escape the emotional economy of humans and other animals. What then?

05:02

It was then that it struck me that perhaps living like a tree was the only route out of whatever it was that I wanted to escape, and I realize only in retrospect now that it was pretty stupid of me. This journey that you know had come to me about 15 years ago. I would say that I began to identify characteristics of plant life that I wanted to imbibe, and in doing so I began to ask myself was I abnormal in harboring such an uncommon ambition to become a tree. So that was the question that was I abnormal in harboring such an ambition? So I kept it a secret from the world, from my family, from friends. But what I began doing was looking for people, writers, artists, thinkers, scientists, philosophers who had exhibited a similar ambition, who had exhibited a similar ambition. How I became a tree is a documentation, I think, of that search an emotional, intellectual and spiritual desire to live like a tree.

06:15 - Jonathan (Host)

Your book starts with a glorious chapter relating to tree time, which is going about the world in a way that doesn't actually measure time, at least not in the ways we are accustomed to in our modern lives, and I now wholeheartedly believe in tree time and I'm trying to get the rest of the world to agree. You write about tree time as an antidote to human urgency. What does tree time mean to you?

06:45 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

I'm smiling, you know, listening to your question.

06:49

You know the phrase tree time came to me, I think, from a sense of deprivation, and I'm very happy to see its adoption and adaptation in various books and essays, of course, but every time I encounter the phrase now, I realize that this is an ideal, an extremely human-centered understanding of time, and almost an unachievable one.

07:19

I'll tell you how this came to me an unachievable one. I'll tell you how this came to me. It came to me while I was on a bus, on the highway, on a commute from home to work or it might have been from work to home looking at land being taken over by real estate developers, trees being felled, agricultural land being snatched to make homes and farmhouses for the wealthy. And, as I say in how I Became a Tree, it was impossible to force the plants and trees in these construction sites to grow, even though the buildings could grow with the energy of concrete and capital. Tree time, that phrase, is an aspiration. It is meant to remind me and now that you say, you're part of the group, so it is meant to remind me, and maybe us, of the comparatives and superlatives that make time speed A tree, a plant, grass, anything from the natural world is not a tube of toothpaste, so tree time. I posit against that kind of understanding of time.

08:36 - Jonathan (Host)

And that's very difficult In our culture, which seems obsessed with speed and output. What does it mean to choose stillness? Can slowness be radical or healing? And how practical is it? How might we begin to implement this tree time into our daily lives?

08:54 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

It is hard because I think most of us have the desire, but not the means, to resist the speed that bulldozes our lives. Our livelihoods seem to have become dependent on speed, not slowness. No employer sends us a note of appreciation for being slow, as we know. You'd have noticed that anything that comes from a culture of slowness, you'd have noticed that anything that comes from a culture of slowness, whether it's art, genres of music, literature, gardening, sewing, knitting, cooking, all of these have been relegated to a position of beggarliness where we need to beg from possible patrons, whoever that might be, you know, the state, other agencies for their time and indulgence, so that we could live and create from this culture of slowness.

09:53

One way, since your question is about resistance, one way of resisting this, I suppose and, Jonathan, I say this only from the very limited perimeter of my own experience so one way of resisting this is perhaps to pay attention. I've said this often to my students that attention is affection. And by noticing, by observing observing anything and everything, for anything and everything is really worth our attention we notice how alive we are. This awareness of being alive is like a rush of blood. It keeps us aware and alert for joyfulness, which is what I think our ambition is, our shared, common, universal, if I may use that word. That ambition is for joy, and joyfulness is a form of alertness. So I think we need to resist to be able to partake of this joy.

10:53 - Jonathan (Host)

It's so important and enhances our lives in so many ways. Going a little deeper with that joyful awareness?

11:11 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

then can you tell us how does tree time influence your own writing process or way of moving throughout the world?

11:26

Here I must confess that this has been told to me by quite a few people, that the rhythm of tree time is often the rhythm of my attention both attention, because both attention and distraction are for me often the same thing. Being distracted is also a form of attention and an act of noticing. So, while speaking to you, when we we began talking, the setup on Zoom, the settings in Zoom, is such that it's only the foreground that we are actually meant to notice. That means that I was supposed to only look at your face, but I asked you a question about a statue of the Buddha in the background, so I was distracted for a moment, and I think that distraction is also very necessary to the process of attention. And that, for me, is also how I understand honesty honesty in writing, honesty in any form of creative practice. So it dictates this understanding of honesty and its relationship with attention and distraction, dictates how I live and love and write and create and, who knows, maybe even how I sleep.

12:40 - Jonathan (Host)

I love that. I'm glad that you brought that up it's interesting because the world is full of distractions but also set up to take those distractions away. And before you came on, I was playing with my backgrounds and you can blur the background and I had that for a moment, so you wouldn't have been able to see anything there. And the reason I unblurred it is, yes, to give you that visual. Maybe there's something to look at to find peace or to have a thought or inspiration, or something like that.

13:09 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

I think it's analogous to what Matthew Hall calls plant blindness that after this conversation it is possible that I would remember you and the Buddha always together, sometimes thinking of the Buddha and the artwork on the wall that you have in your room in the background. Sometimes you would notice that you come back from meeting someone and if someone were to ask you, if your partner were to ask you, what were the trees in the drawing room or the living room, chances are we often forget because, like the Buddha in the background, like the zoom settings, which asks us to blur the background, a part of our human conditioning has been to blur the trees, the plant life, out of our consciousness. So, because we're talking about plant life and attention and distraction, I think all of these come together in the way we experience and enjoy the world in its fullness rather than just with focus. Focus, I think, is a very capitalist word and we must try to wean ourselves away from focus. Also, being focused all the time might be damaging to our nervous system.

14:30 - Jonathan (Host)

And that fullness also means truth, as you were speaking about before, as being honest with who I am, what is on my wall, this is me.

14:41 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

Yes.

14:42 - Jonathan (Host)

Well, we're talking about blurring backgrounds. So that leads me to AI, which is coming up in all of our worlds. I'm sure, as an author, a writer, a teacher, that AI comes into discussions and things that you have probably all of the time that you have probably all of the time. As we increasingly blur the lines between human and machine, your work and your book encourages us to blur the lines instead between human and plant. What do you think gets revealed when we shift that boundary instead?

15:18 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

it's a wonderful question. Thank you, Jonathan. It might it must be my unarticulated conditioning in something I took for granted, something that must have been in the air when I was growing up, that derived from a manner of thinking and living that imagines, or believes, that life is in everything. It is perhaps because of my growing up in this culture of thinking that I'm unable to see boundaries that differentiate one species from another. By this I do not mean that a human is a plant, or that a plant is a machine, and so on. I mean that I see more convergences than dissonance. The human imagination is one of the most remarkable machines we have. We can become anyone and anything, and yet we seem to limit ourselves in trying to become only, like, members of our species.

16:23

We've had a few rhetorical devices that facilitate such thinking, even if they imply transferring human registers to other species. These effective registers are also now being imported in the sciences so that scientists can declare today, like they did in March 2023, that plants cry. It's the word that the scientists use that plants cry if they are not watered for more than two days. Maybe empathy is the world I'm looking for, but it's a limited shorthand for what I feel, I become them, I become them all, and it is hard to live as a human because I'm reminded in words and gestures and, of course, by public policies, and you know, both written and unwritten, that this is neither possible nor desirable, this analogical understanding of life forms. But it is important to go to your question. As much as we recognize boundaries and create policies recognizing the rights of every species, I think the reason we once went to fiction to imagine other lives. If we were able to import that aspect, that facility of the imagination, into our day-to-day lives, something would happen that would enrich us and the world we live in.

17:57 - Jonathan (Host)

So if more people embraced becoming a tree, even metaphorically, how do you think our world would change?

18:07 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

I'll try to explain this with a very simple example. In India, for instance, as I imagine in many other places in the world, trees and forests are cut for what the government calls development to build roads and airports and highways and industries. People like you and me, protesters, we are pacified with a ludicrous line of reasoning. The government tells us we will plant 500 trees in some other place to make up for this loss. Can one say this to a human I'll kill your three children, but I'll ensure that three humans are born to some other mother in that neighborhood. So becoming a tree, to use your phrase and mine, would show up this line of thinking to be ridiculous and, of course, heartless. If we were to become the trees, we would not be able to do this.

19:04 - Jonathan (Host)

Right, and it goes into seeing our relationship with trees and the natural world in such a different way as being connected as part of us. So taking that into reading, how might reading, like a tree absorbing, slowly metabolizing over time, change the way we take in news, conflict or even social media?

19:31 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

Again, let me use this word attention. I tell my students that's my religion and those who ask about how I write like this or how I notice what I do, I think it has to do with attention. It might also be aloneness. I don't feel lonely, but I do feel alone and quite often a misfit, everywhere I find myself among people who derive their power from their religious or national or racial identity. The obsession with news, which is basically a form of abstraction, the reason it is easy to pass off anything as news. The nation fetish you know, whether it's America or India, we're going through that stage the fetishization of the nation. The supremacy of our individual nations, all these macro level things that actually do not annotate how we live from moment to moment. Don't look at an Ashotthu tree braving its head out of a crack in a wall and think, ah, brave Indian tree. I'm not aware of being attentive. That consciousness of being attentive would destroy the rewards of attention.

20:58

I've had the habit of looking at and often photographing walls in my hometown as I walk through neighborhoods. In fact, just before speaking to you, I was taking a walk through a neighborhood adjacent to the one that I live in. There's always something new, like there is always something new in a bird's nest, a new branch, something collected from somewhere. No one planted these things for me. I don't go looking for them, but I end up noticing them. They make me smile. What other reward does one need to stay alive? I also find myself noticing the wind a lot. It sounds what it causes to all the forms around me.

21:37

So I think I import, very unconsciously or subconsciously, this understanding, this experience of living in the world to reading and writing practices of my own. And I want to say because you asked about social media and the news I don't watch the news and I don't read newspapers for the news anymore. I stopped about 12 years ago when I found that the distinction between news and what is called fake news almost did not exist anymore. One of my reasons for wanting to become a tree was its indifference to the news cycle.

22:16

As I say in that section, the frenetic speed of the news cycle, the news studio, the news ticker it's like living on a treadmill, the nervous system perennially agitated, there is no rest. A tree, as I said in the book, is a daily wage earner invested in the present. We could try to read and write and create like that to the rhythm of living time. There are rewards to be had there. Like a tree that changes with the seasons, the rewards of reading might be more natural and dependent on the weather as well, instead of the inert, publicity-driven reading lists that rule our reading habits.

22:58 - Jonathan (Host)

In the book Becoming a Tree, you write many reflections on gender and care, and I'm wondering how did the book, or did the book help you rethink your relationship to the body, or to softness as well as safety?

23:16 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

Yes, I know why you mentioned safety. I think in the first page or the first paragraph of the book. I wrote it a long time ago and I don't remember it. Yes, safety, particularly in South Asian cultures where, you know, women are not really safe, not during the day and certainly not after sundown.

23:37

It was a scholar of care who pointed this out to me what you said just now, that care seems to be a primary axis around which my thoughts and feelings run. This too might come from a sense of deprivation, perhaps because I sought care and needed it immensely at certain periods in my life and didn't get it. I became a person who wanted to be a carer or caregiver to whoever I could. A school friend of mine her name is Reshmi told me a few years ago that she remembers this about me from when I was little in school. So caring is a natural instinct, at least for me, and I have the superstitious belief that if everyone is well everyone around me, by which I mean this entire neighborhood of this planet If everyone is well, I will be well too. So there's a form of self-centeredness in my desire to care for those I know and also don't know. I have to tell you this. This often irritates my family and friends.

24:45

They use a phrase, an idiom in Bangla for my actions. It's called opatredan. In a rough translation it would be giving or donating to a person or place that is undeserving of such philanthropy. I don't know, that's a poor translation. I suppose my response to that is does a tree deny us its goodness and generosity because we are bad people? If you're a good person, the tree will give you shade. If I'm a bad person, the tree will give me shade as well. So, to answer your question, my care extends to all, to everyone, like the trees does. It is identity agnostic About my relationship with the body. Well, I wish I was more plant-like, more indifferent to judgment about my appearance, invested only in my health, which is how I imagine trees grow and find form. And yes, I'd like to imagine and believe that a tree isn't as exhausted as I am, in spite of the cycles of recuperation and recovery that it has to go through periodically.

25:53 - Jonathan (Host)

I do want to touch on your latest book as well, which is entitled Plant Thinkers of 20th Century Bengal, and within the book, you explore how Bengali writers and philosophers drew insight from plant life. It's a wonderful book, filled with numerous stories of people from various walks of life and how plants and trees were a part of their daily lives. In your words, what makes someone a plant thinker? What makes someone?

26:28 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

a plant thinker.

26:28

The phrase isn't mine, jonathan.

26:30

I owe it to Michael Marder, who used it for a cluster of philosophers who had thought about plants the way most had about the human.

26:42

I suppose I borrowed it from Michael to write about a lineage of thought about plant life that I thought was peculiar to a moment in history in 20th century Bengal. Also, I was importing the term plant thinker to not think of professional philosophers, like Michael Marder had written, but scientists, artists, poets, writers, filmmakers, none of whom were environmentalists, but people who at that time were formed by a certain kind of plant philosophy that was in the air. That's what I think of plant thinkers, and I think there are lots of plant thinkers in the world around us, and these are not necessarily professional plant, a professional botanist or professional philosophers, and it's important to have their voices heard. And before we began recording, that is why I said thank you for doing something such as this podcast, that we have an archive where we can go to listen to different ways of thinking about plant life. So I would say, to answer your question, all the people you've spoken to for this podcast would be plant thinkers.

27:56 - Jonathan (Host)

Yes, and I think your books also encourage people to be plant thinkers. It also, I think, plants the seed for lack of a better term for people to become plant thinkers as well, because it is a wealth of ideas and inspirations having to do with trees, but from your specific perspective is made universal and I think I would imagine anyone reading the book will find parts of themselves within it as well. How I Became a Tree was first published in 2017. How has your relationship with trees evolved since writing the book?

28:36 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

Friends and strangers, and now from all across the world. They send me photos and news and research reports about new discoveries about plant life. It's as if they're informing me about a relative. I feel very touched by these messages and these photos. I work in the garden more than I have ever before. Last year I saw pomegranates flower in the garden for the first time in my life. My relationship with plants and trees and grass and moss is outside the ambition and logistics of ownership, of control and proprietorship. I find it calming to be in such a relationship and I feel grateful to have had this opportunity to record my thoughts about the plant world, about plants. I think without having gone through this process of recording these thoughts, I might not have gotten to where I am, not just in relationship with the plant world, but this relationship with myself as well.

29:45 - Jonathan (Host)

If the book were being published today. Are there ideas or reflections you might add or change?

29:52 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

It is possible that I would have called the book how I Became Grass and not how I Became a Tree, grass and not how I became a tree, for it was only a few years after the book was published that it occurred to me that it wasn't really a tree that I had wanted to become. It was grass, the rhizome, jibunonando Das's grass this poet I write about in Plant Thinkers of 20th Century Bengal, whitman's grass, leaves of grass, deleuze and Guattari's grass, and the grass outside my window that I wanted to become. I also realized that the structure of the book, where you can read any section and in any order, that it wasn't a narrative where one page must follow another. This was rhizomatic, so I probably call it that.

30:42 - Jonathan (Host)

I love that. I'm glad you called it how I Became a Tree, but maybe there's another book, maybe that's the sequel. Beautiful Well, shumana, thank you so much for joining us today. Your writing and works have sparked our imaginations and shown us a better, more sustainable and joyful way to live. We appreciate the way you blend such academic rigor and creative thinking with inspiring wonder and an appreciation for life and the deep connection that is innate in all living things. So this conversation has really been a pleasure, thank you.

31:18 - Sumana Roy (Guest)

Thank you for having me on your podcast, Jonathan. I enjoyed speaking with you very much.

31:32 - Jonathan (Host)

Sumana's words are going to stay with me for a long time. She gave us so much to think about, to question, to turn over in our minds. What I keep coming back to is her focus on attention and distraction and how both can shape the joy we find in everyday life. And then there's the idea of tree time. It feels so different from the way I usually move through my days, ruled by schedules, calendars and clocks. I'm always asking myself how long will it take if I go this way. Instead of that, how fast can I get my work done? How little sleep can I get away with so I can still stay up to watch a movie? Tree time turns all of that upside down and it makes me wonder what would it mean for me to live more like a tree? That question also resonated with our very own Dori Robinson, who is deeply moved by Sumana's chapter on tree time as well. I'm so glad she's going to share her own reflection with us. Now let's listen.

32:50 - Dori (Co-host)

I am always late, unless it's a rehearsal, a recording session or a class. I'm behind. Class I'm behind. Maybe it's ADHD, maybe it's people pleasing, maybe it's the illusion that 10 spare minutes can hold one more task, but inevitably I lose myself in the present moment, thereby derailing the next. Reading

33:16

Tree Time struck me deeply. The idea that trees have their own time and are never late, never early, simply evolving exactly as they are meant to, according to their roots, the sun and the rain they receive, the air they breathe and the soil they grow in. Their algorithm is entirely their own and cannot be rushed or slowed. Who would scold a tree for growing too slowly or blossoming too soon? Sometimes we choose change and sometimes change overtakes us.

33:55

Five years ago, on my birthday, I had resolved to figure out how to have a child on my own. I had always imagined raising a child with a partner, but several relationships and an ungodly amount of dates later I had not found my person. I was single, aware of time passing and worried that the window might close. Then COVID arrived and time stopped. My search froze. The first time I realized my perception of time had changed was during the height of the pandemic. Suddenly, we were all forced to slow down. The urgency of commuting, the daily scramble of life, the crowded schedules fell away. We had no choice but to move at a different pace. Time might have stopped in the outside world, but it continued to accelerate inside me.

34:50

I felt late, desperate to catch up. The moment I could return to working in person, I threw myself into the deep end, determined to succeed as a professional theatre artist, pushing myself to prove that I belonged. Rehearsal schedules became my clock, curtain times my calendar. It was thrilling to lose myself in gig after gig. But beneath the energy was a quiet grief. I had filled the space where a child might have been with the rush of constant motion. I had replaced growth for busyness, arrival for applause.

35:28

But even trees, in their long wisdom, do not try to bear fruit in every season. All the while, my body whispered its own warnings: brain fog, extra pounds, heightened emotions. Friends spoke about life changes and Instagram offered an endless scroll of supplements and advice Do this before it's too late. I panicked, desperate to keep blooming. But trees do not panic. They understand that rest is as essential as fruiting. When I am most consumed by my phone is when I am at my worst. Doomscrolling convinces me that I am perpetually behind. But the trees wait patiently outside my window while I scroll. Their time is unchanged, unhurried, even as I try to outpace my own. And then, thankfully, I finally step outside. I noticed the birches, the pines, the oak. They leaf, fruit, rest and shed in their own rhythm.

36:35

Last week my nephew bravely left for college and I am unbelievably proud of him. When he was born I'd imagined that my children would be just a few years behind him, that the cousins would play together side by side at holidays, but last week, as he rightfully began a new chapter, I realized that this door had closed. Perhaps I may still have children in some way, shape or form, but the time for the cousins to be playmates is over. That particular time has passed. I can't help but feel hollowed out, as if time has removed my insides.

37:14

But I am reminded that some trees bear fruit for only 25 years, a blink in a century's long life. Their cycles come as they come, and me I still ache to bloom in ways I wish I had 10 years ago. Yet I will try to hold grief in one hand and abundance in the other. Friendships, creative kin, a home and a garden, all the roles I love daughter, sister, aunt, teacher, director, storyteller. I will try to breathe, to trust that my becoming has its own rhythm, its own cycle. If I know anything about trees, it is this. They will not rush me, they will simply stand with me in the season I am in.

38:20 - Jonathan (Host)

As we bring today's episode to a close, I keep returning to the way Sumana Roy's how I Became a Tree asks us to see the world differently, to notice the spaces between attention and distraction, to imagine time not as a clock but as a living rhythm. Time not as a clock but as a living rhythm. Her words, along with Dori's reflection, remind us that becoming more like a tree isn't about leaving our human lives behind. It's about allowing ourselves to slow down, to root more deeply and to discover joy in the simple act of being present. Thank you to all of you for spending this time with us and for listening truly listening in tree time. Until next time, may you find a moment of stillness and maybe even a little wonder in the trees around you.

This week's episode was written and recorded in New York on the land of the Lenape tribes. This episode was written, edited and produced by Jonathan Zautner with Dori Robinson. To learn more about our podcast and episodes, please visit treespeechpodcast.com and consider supporting us through our Patreon.

39:49

Every contribution supports our production and we'll be giving gifts of gratitude to patrons of all levels. Please also consider passing the word and rate and review us on Apple Podcasts. Every kind word helps. A very special thank you to Sumana Roy for joining us today. Please look for her books, including How I Became a Tree at your local bookstore. And thank you for joining Tree Speech today.